Next Generation Clinical Integration Networks: Lessons Learned

Rob York is a Senior Vice President of Kaufman, Hall & Associates, LLC, and leader of the Population Health Management division in the firm’s Strategy practice. He provides strategic services for a range of healthcare industry clients, including payers, physician organizations, academic health centers, large healthcare systems, public/safety-net providers, and community hospitals.

Mature clinical integration networks (CINs) are moving beyond basic performance improvement activities to develop contracting strategies with multiple payers, achieve scale across larger populations and geographies, and assume greater financial risks for outcomes. These advanced value networks or “Super-CINs” are also moving beyond many commonly held beliefs. As more CINs come on board, lessons learned by startup and early stage CINs are propelling the conversation to focus on care delivery transformation. Three of those lessons learned along the journey to population health follow.

Adopting a Successful Case Study Isn’t Enough: What has succeeded in one market will not necessarily succeed in your market. In some cases, the approach of pioneering CINs such as Advocate, along with FTC requirements, have been used as blueprints. What we have learned, however, is that business and clinical readiness, state laws, payer role and agreements, partner responsibilities, information and technology capabilities and many other factors vary significantly by market and CIN. Many of the “Super-CINs” are operating across a variety of regions and must develop unique approaches in each market. Requirements for payer contracting strategies, care standardization and care management infrastructure will look very different depending on the progress of clinical integration and the specifics of the local market.

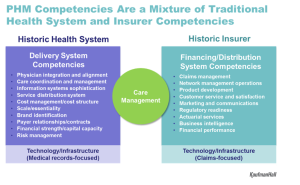

No One Can Do it Alone: While there continue to be stand-alone hospitals and independent physician practices, most are creating partnerships at some level. Historic views of the payer-provider relationship are changing on both sides. There is more willingness to have an open conversation because payers and providers need each other to make population health management work. The relationship varies by market – in some, payers are driving the design of the value network, and in others providers are taking the lead. Rather than staying in their traditional siloed roles, both are coming to the table to design new approaches to care management. Payers have tools and information sets, and providers need to enhance care management. In addition, nontraditional players are becoming part of the landscape, such as DaVita HealthCare Partners, which operates medical groups and specializes in care management, and which has sought to partner with payers for population health management.

No One Can Do it Alone: While there continue to be stand-alone hospitals and independent physician practices, most are creating partnerships at some level. Historic views of the payer-provider relationship are changing on both sides. There is more willingness to have an open conversation because payers and providers need each other to make population health management work. The relationship varies by market – in some, payers are driving the design of the value network, and in others providers are taking the lead. Rather than staying in their traditional siloed roles, both are coming to the table to design new approaches to care management. Payers have tools and information sets, and providers need to enhance care management. In addition, nontraditional players are becoming part of the landscape, such as DaVita HealthCare Partners, which operates medical groups and specializes in care management, and which has sought to partner with payers for population health management.

This Is More than an Experiment; Success Means Making a Commitment to Go the Distance: Many of the more advanced value networks are recognizing that upside, shared savings are short lived and that the real opportunity is associated with the assumption of risk. Early on, some providers chose not to assume risk because of challenges such as capital requirements and the need for cultural change. However, the urgency has been ramped up by external forces such as the intention of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to move 50 percent of its payments into value-based arrangements by 2018. CINs and accountable-care organizations entering the market today must realize that a commitment to go the distance is essential. For example, organizations need to develop a contracting strategy that encompasses a variety of commercial, CMS and direct-to-employer agreements; define a care management model; and invest in a care management platform with key partners. Success will be driven by hyper focus based on your market characteristics and your organization’s capabilities, chosen role in population health management, and level of clinical integration.